Imagine that U.S. Supreme Court nominees are only confirmed if the same party holds the presidency and the Senate. What is the expected number of vacancies on the bench in the long run? You can assume the following:

- You start with an empty, nine-person bench.

- There are two parties, and each has a 50 percent chance of winning the presidency and a 50 percent chance of winning the Senate in each election.

- The outcomes of Senate elections and presidential elections are independent.

- The length of time for which a justice serves is uniformly distributed between zero and 40 years.

Solution:

Here is a broad-strokes “solution” that, while it turns out to be just a pretty good approximation, contains the essentials of the correct approach.

Every election has probability $1/2$ of giving joint control to one party or the other for the next two years. When that happens, all vacancies are filled immediately, and for those two years, new vacancies are filled instantly.

When a seat goes vacant, then, there’s close to (this hides dark difficulties, to be explained soon, that are significant if not hugely so) probability $1/2$ that it’s during a joint-control cycle, and so the duration of the vacancy will be $0$, and probability $1/2$ that it’s a divided-control period so that the seat will be vacant for the remainder of the current election cycle (a period of close to (!) $1$ year on average) plus however long it takes for an election to produce joint control. The expected number of elections to reach the first joint-control outcome is the same as the expected number of tosses of a coin to get a heads, which is $2$ (see the Appendix to see why). The second election happens $2$ years after the very next election after the seat goes vacant. Therefore the expected duration of the vacancy is (close to) $\frac{1}{2}(1+2)$, or $3/2$.

The probability that a given seat is vacant at any one time is (close to) the ratio of expected vacancy length to the sum of expected term and vacancy lengths:

\[\frac{\frac{3}{2}}{20 + \frac{3}{2}} = \frac{3}{43}\]That value is also (close to) the expected number of vacancies in that one seat at any one time. And so the total expected number of vacancies at any one time is (close to) nine times that, or $27/43$, which is is about $.628$.

But That’s Not Quite Right

There are two simplifications in the reasoning above. First, it’s not true that a randomly selected term is exactly equally likely to end in joint- and divided-control cycles. Second, term end-times are not exactly uniformly distributed as to where they fall within divided-control cycles, nor within joint-control cycles (the one entails the other given that end-times are uniformly distributed overall). The second inexactness turns out to be negligible in effect, nudging our answer within $.001$ vacancies, whereas the first is significant to the tune of more than $.02$ vacancies.

The fact that any given term (after the very first ones, which we can ignore as negligible in the long term) starts in a joint-control cycle—because only then will the Senate confirm a nomination—entails that the probability is a little more than $1/2$ that it will also end in a joint-control cycle, because there is probability $1$ that it ends in joint control if it ends in the same cycle in which it began (of which there is some positive probability up to $1/20$), and $1/2$ if it ends in any later one.

To cut to the chase, this makes the average duration of a vacancy not $1.5$ but about $1.\overline{4}$ and the expected number of vacancies not $.628$ but about $.606$. Details follow.

Let’s forget about years and calculate in time units of (two-year) cycles. Term durations are uniformly distributed between $0$ and $20$ cycles, with an expectation of $10$. Each term (after the starting ones) starts some time $t$, between $0$ and $1$, into a joint-control cycle. If it ends in the same cycle ($(1-t)/20$ chance of that), there is probability $1$ of ending in a joint-control cycle. If not ($1-(1-t)/20$ chance), there is probability $1/2$ of that. So a term starting $t$ into a cycle has the following chance of ending in a joint-control cycle:

\[\frac{1-t}{20} \times 1 + \left(1 - \frac{1-t}{20}\right)\times\frac{1}{2} = \frac{21-t}{40}\]And so a term has chance:

\[1 - \frac{21-t}{40} = \frac{19+t}{40}\]of ending in a divided-control cycle.

The many terms that start at the beginning of joint-control cycles (after some divided-control ones), have end-times uniformly distributed between $0$ and $20$ cycles after the cycle start-times, and so in particular the end-times that fall in divided-control cycles are uniformly distributed across them. So such terms that end in divided-control cycles have expected vacancies of exactly $3/2$ cycles.

But terms that start some positive time $t$ into a (joint-control) cycle and end in a divided-control cycle have a slightly higher than $t$ chance of ending at times before $t$ than ending at times after $t$ into a cycle. Such terms have end-times uniformly spread over the periods that consist of the $19$ complete cycles within their possible durations, plus the initial $t$ portion of the cycle following those $19$. That means that such a term has probability $20t/(19+t)$ of ending less than $t$ into its end cycle, which is a bit greater than $t$.

Taking that complication explicitly into account would involve finding an expression for the nonuniform distribution of such end-times, which looks to me like a task better suited to the talents of others (and I’d be interested to know if others have worked it out!). Less imposing is the task of showing that, to a very close approximation, the distribution is in fact uniform; that is, that we can assume that it is uniform with very little effect on our calculation.

Every term that ends in a divided-control cycle (every “TEDC”) has a most-immediate predecessor term (perhaps itself) that started at the start of a joint-control cycle. The first-generation TEDCs themselves start at the starts of cycles, and so have their ends uniformly distributed within cycles, producing uniformly-distributed starting points for second-generation TEDCs.

To find out how the ends of second-generation TEDCs (and so the starts of third-gens) are distributed within cycles, we calculate the chance that a TEDC with start time $t_1$ into a cycle ends less than $t_2$ into a cycle. If $t_1 \leq t_2$, then that chance is:

\[\frac{19t_2+t_1}{19+t_1}\]and if $t_1 \geq t_2$, the chance is:

\[\frac{20t_2}{19+t_1}\]So the chance that second-gen TEDCs, which have uniformly distributed start times $t_1$ into a cycle, end by $t_2$ into a cycle is:

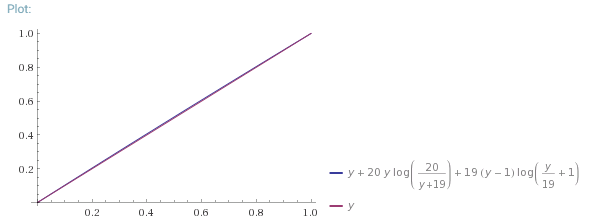

\[\int_{t_1=0}^{t_2} \frac{19t_2+t_1}{19+t_1} dt_1 + \int_{t_1=t_2}^1 \frac{20t_2}{19+t_1} dt_1\] \[= (19t_2-19)\ln\left(\frac{t_2+19}{19}\right) + t_2 + 20t_2 \ln\left(\frac{20}{19+t_2}\right)\]Here’s a graph of this function together with the function $f(t_2) = t_2$, which characterizes the uniform distribution.

As you can see, the distribution is so extremely close to uniform that to a very good approximation we can assume that second-gen TEDCs too have end times uniformly distributed in cycles, and hence that so do third-gen, and so on. That is, we can assume that to a very good approximation all term end-times are uniformly distributed as to where they occur within cycles, whichever kind of government they end in. Whew.

To calculate the expected length of a vacancy, we’ll need to do two things: determine the distribution of term start-times, and calculate the expected length of a vacancy as a function of the start-time $t$ of the previous term. Let’s start with the latter. We established above the chance ($(19+t)/40$) that a term starting $t$ into a cycle ends in a divided-control cycle. Because we now know that the distribution within that ending cycle is basically uniform, we expect the term, if it does end in divided control, to end halfway though a cycle, and so the expected vacancy is $3/2$ cycles—that is, half a cycle plus the one full cycle needed to produce the two elections that are expected to generate the first joint-control government.

Thus the expected length in cycles of a vacancy after a term starting at $t$ is:

\[\frac{21-t}{40}\times 0 + \frac{19+t}{40} \times \frac{3}{2} = \frac{3(19+t)}{80}\]Now to determine how term start-times are distributed. There are two cases. The terms that start some positive time into a joint-control cycle are very nearly uniformly distributed within such cycles (this follows from the same fact about endings in divided control). And there are terms that start right when joint control newly occurs (i.e., $t=0$). We need to know what proportion of all terms are of this latter kind.

The terms that start at the start of a cycle (after the very start, and with exceptions of probability zero) are the successors of terms that end in divided-control cycles, and so there are exactly as many of the former as of the latter. Let $p$ be the probability that a term starts at the start of a cycle, which is also the probability that a term ends in a divided-control cycle. We will find $p$ by relying on both of those facts about it.

A proportion $p$ of terms start at the start of a cycle, and each has chance $19/40$ of ending in a divided-control cycle. And the remaining $(1-p)$ of terms have start-times uniformly distributed between $0$ and $1$ cycles into a cycle, with chance of ending in a divided-control cycle being $(19+t)/40$. So the overall probability of a term ending in a divided-control cycle is:

\[p = p \times \frac{19}{40} + (1-p) \int_{t=0}^1 \frac{19+t}{40} dt\] \[= \frac{19}{40}p + \frac{39}{80}(1-p) = \frac{39}{80} - \frac{1}{80}p\] \[p = \frac{39}{81}\]So $39/81$ of terms start at $t=0$. Thus the overall expected vacancy duration is:

\[\frac{39}{81} \times \frac{3(19+0)}{80} + \frac{42}{81} \times \int_{t=0}^1\frac{3(19+t)}{80} dt\] \[= \frac{2223}{6480} + \frac{91}{240} = \frac{13}{18} = .7\overline{2}\]That’s in cycles, so the average vacancy is $13/9$, or $1.\overline{4}$ years.

The expected number of vacancies at any random time, then, is:

\[9\times \frac{\frac{13}{9}}{20 + \frac{13}{9}} = \frac{117}{193} \approx .606\]Verified as accurate to within a thousandth by simulation (code below).

Appendix: How Many Flips to Get a Heads?

Flipping a fair coin, the expected number $E$ of flips when the first Heads occurs is $1/2$ times $1$ (half the time, it’s the first flip) plus $1/2$ times $(1+E)$ (the other half of the time, you have one Tails and are back where you started, expecting to need $E$ more flips). So:

\[E = \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{2}(1+E)\] \[E = 2\]Code (Python):

from random import randint,uniform

num_reps = 100000000

accum = 0

num_vacancies = 0

duration_accum = 0

# A running list of the vacant seats, starting with all of them.

Vacancies = [0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]

# A list of the times justices in the 9 seats are due to retire

# or die yes I went there. We use num_reps as a dummy value to

# start.

Expiration = [num_reps]*9

for rep in range(num_reps):

# the current "rep" is the number of 2-year periods that have

# passed.

# Here we will figure the average number of vacancies since

# the last election, including new vacancies.

# If there were vacancies after the last election it's

# because there is not joint control, so those vacancies

# remain. So the Average number of vacancies over this past

# 2-year cycle is at least:

AvgVacancies = len(Vacancies)

# Create a list for the expiration times seats will

# have going into this election.

NewExpiration = [num_reps]*9

for i in range(9):

# Looping through the seats

if rep-1 < Expiration[i] <= rep:

# Seat i has been vacated since the last election

if SameParty:

# Seat was filled as needed until due to expire after

# this election, so it's been continuously occupied,

# and adds nothing to average vacancies. For each filled

# vacancy we increment num_vacancies. We leave

# duration_accum alone, as the duration is 0.

NewExp = Expiration[i]

while NewExp <= rep:

# Seat went vacant before now, so:

num_vacancies += 1

NewExp += uniform(0,20)

NewExpiration[i] = NewExp

else:

# Seat has been unfilled for (rep - Expiration[i]) reps,

# adding that same amount to the average number of

# vacancies since the last rep.

AvgVacancies += (rep - Expiration[i])

# This is the only place we add to the list of vacancies.

Vacancies.append(i)

# We keep track of when the seat went vacant so that we

# can record the duration of the vacancy when it's filled.

NewExpiration[i] = Expiration[i]

else:

# Two cases here. (1) Seat remains occupied so there's no

# effect on AvgVacancies. (2) Seat was already vacant as of

# the last election (or as of the start) and remains in

# Vacancies, so AvgVacancies has already counted it. We track

# when it will or did expire.

NewExpiration[i] = Expiration[i]

Expiration = NewExpiration

# We add up the average numbers of vacancies between reps, and will

# divide by num_reps to give the overall average.

accum += AvgVacancies

# Hold elections

SameParty = randint(0,1)

if SameParty:

# Fill empty seats

for i in Vacancies:

# Again we increment num_vacancies upon filling one.

num_vacancies += 1

if Expiration[i] > rep:

# These are the initial vacancies

duration_accum += rep

else:

duration_accum += rep - Expiration[i]

Expiration[i] = rep + uniform(0,20)

# This is the only place seats are removed from the vacancies list.

Vacancies = []

print("Average number of vacancies:",accum/num_reps)

print("Average duration of a vacancy:",2*duration_accum/num_vacancies,"years")