- If you break a stick in two places at random, forming three pieces, what is the probability of being able to form a triangle with the pieces?

- If you select three sticks, each of random length (between 0 and 1), what is the probability of being able to form a triangle with them?

- If you break a stick in two places at random, what is the probability of being able to form an acute triangle — where each angle is less than 90 degrees — with the pieces?

- If you select three sticks, each of random length (between 0 and 1), what is the probability of being able to form an acute triangle with the sticks?

Let’s add, just for fun:

If you break a stick in three places at random, forming four pieces, what is the probability of being able to form a quadrilateral with the pieces?

If you break a stick in $n$ places at random, forming $n+1$ pieces, what is the probability of being able to form a $(n+1)$-gon with the pieces?

Solutions

1

If you break a stick in two places at random, forming three pieces, what is the probability of being able to form a triangle with the pieces?

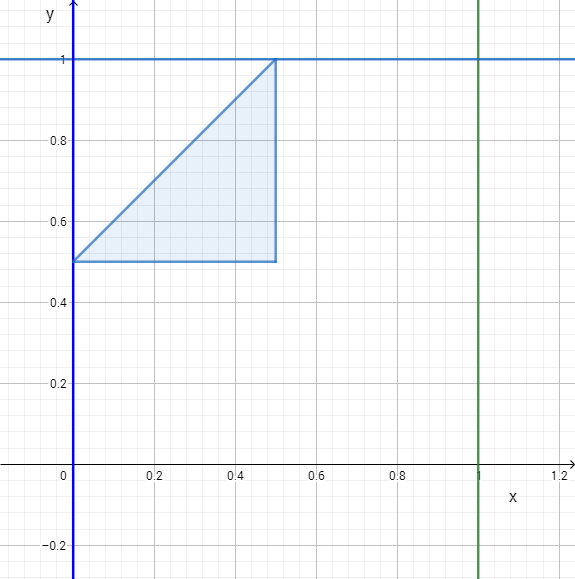

The question is, if $x$ and $y$ are random numbers between $0$ and $1$ (with the obvious unstated assumption that the distribution of probabilities is uniform), how likely is it that the differences between them and $0$ and $1$ are such that none is greater than $1/2$? We can ignore (in this and the other problems) the possiblity that $x=y$, because it has zero probability. If $x$ is less than $y$, those differences are $x$, $y-x$, and $1-y$; each must be less than $1/2$. Each of these three inequalities tells us that the points in the $xy$-plane lie to one side of a straight line. Together they determine a triangle of area $1/8$ (it’s half of a quarter of a unit square).

Our assumption that $x>y$ determines a region of area $1/2$, and since the case of $y>x$ is symmetrical, we conclude that the proportion of $(x,y)$ pairs suited to making triangles is $1/4$.

2

If you select three sticks, each of random length (between 0 and 1), what is the probability of being able to form a triangle with them?

Now we’ve got three numbers, $x$, $y$, and $z$, and so we are working in the unit cube. Each of the three constraints now tells us that the triangle-making points are to one side of a plane:

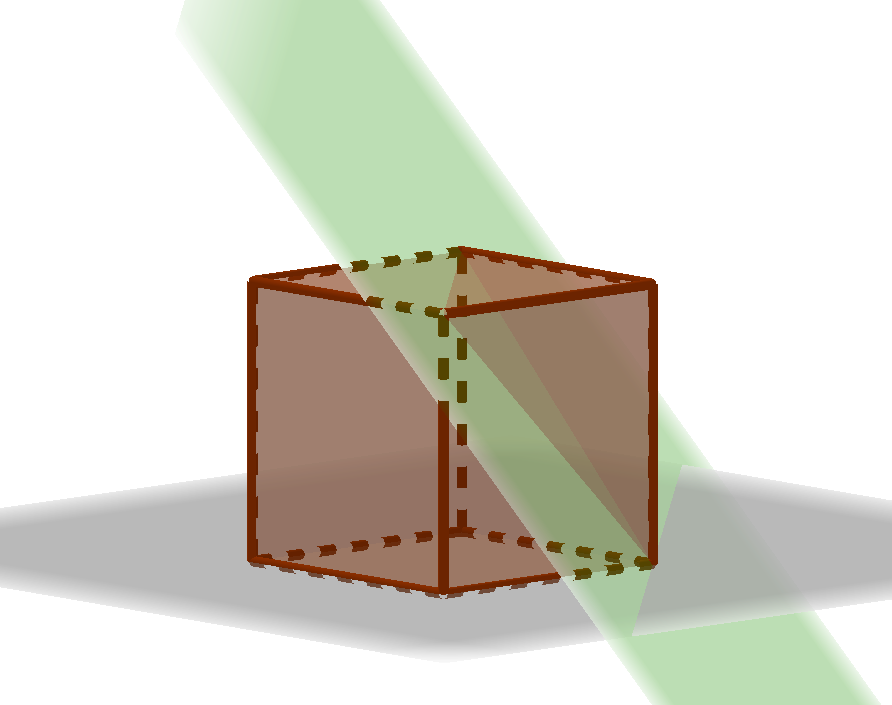

\[x < y+z\] \[y < x+z\] \[z < x+ y\]Each of these planes slices from the cube a pyramidal corner, whose own vertices are four of the cube’s. The pyramids don’t overlap, because at most one of the inequalities can be false.

The volume of a pyramid is one-third of the base area times the height. The base area of the lopped pyramids is $1/2$ and the height is $1$, so the volume is $1/6$. Three of these make up a volume of $1/2$, and so we conclude that half of the triples of random lengths allow us to form a triangle.

3

If you break a stick in two places at random, what is the probability of being able to form an acute triangle — where each angle is less than 90 degrees — with the pieces?

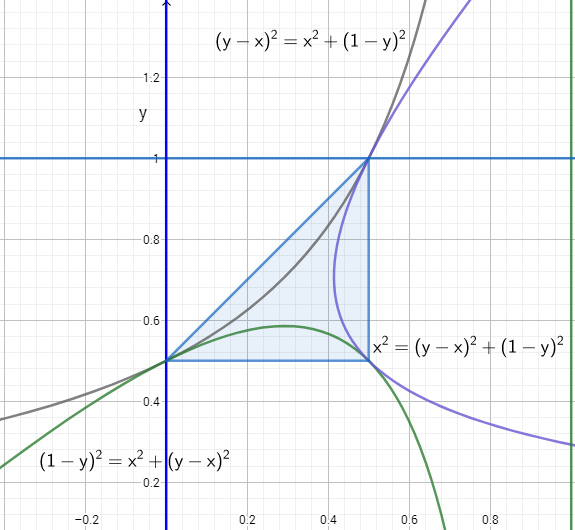

We’re back to the unit square in the $xy$-plane, and again, assuming that we’re in the $1/2$ probability region where $x<y$, if we can form any triangle, the point $(x,y)$ has to be inside the triangle we found in the first problem. Acuteness forces three new constraints, because each side of the triangle has to be too short to be the hypotenuse of a right triangle:

\[x^2 < (y-x)^2 + (1-y)^2 \Longleftrightarrow x < y + \frac{1}{2y} -1\] \[(y-x)^2 < x^2 + (1-y)^2 \Longleftrightarrow y < \frac{1}{2-2x}\] \[(1-y)^2 < x^2 + (y-x)^2\]These tell us that the triangle-prone points are inside a curvy triangle formed by three hyperbolas.

The three areas trapped between the hyperbolas and the outer triangle must have equal areas. The right-most and lowest regions are obviously reflections of each other. The upper-left and right-most regions are not, but they have the same width (in the $x$ dimension) at every value of $y$ (namely $1/(2y) - 1/2$), and therefore, by the ever-useful Cavalieri’s Principle, have the same area.

So it will suffice to find the area of one of them, and we will focus on the upper left. That hyperbola (which has the equation $(1-x)y = 1/2$) is just the ordinary $xy=1$, except shifted to the right by $1$ unit, mirrored about the $y$ axis, and scaled linearly by a factor of $1/\sqrt{2}$. Thus the area in question is half of the area of the geometrically similar region in the hyperbola $xy=1$.

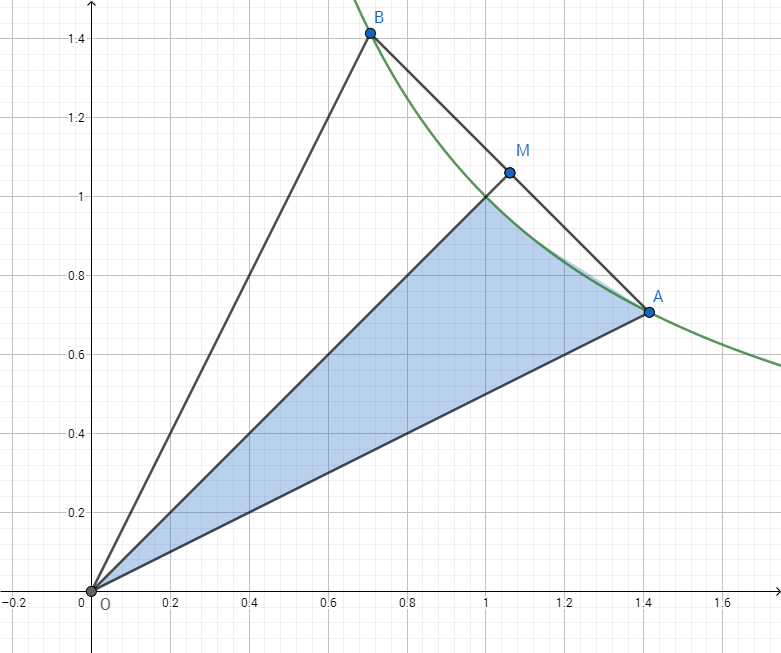

The area of the shaded region (called a hyperbolic sector) is the natural logarithm of the $x$ coordinate of point $A$; so it is $\ln(\sqrt{2})$, or $\ln(2)/2$. The area of the triangle $\triangle OAB$ is $\overline{AM}$ times $\overline{OM}$, or $1/2$ times $3/2$, or $3/4$. so the area of the trapped region of interest is $\frac{3}{4} - \ln(2)$. Scaling that back to actual size, we get:

\[\frac{3}{8} - \frac{\ln(2)}{2}\]The area of the curvy triangle is the area of the straight triangle minus three of those regions:

\[\frac{1}{8} - 3\left(\frac{3}{8} - \frac{\ln{2}}{2}\right) = \frac{3\ln{2}}{2} - 1\]And the proportion of the region of area $1/2$ in which $x<y$ that it occupies, and hence the probability that we can form an acute triangle, is twice that, or the surprisingly small:

\[3\ln{2}-2 \approx 7.944\%\](The one somewhat arcane fact we’ve relied on is that the area of a hyperbolic sector of $y=1/x$ is the natural logarithm of its greatest $x$ coordinate. To deduce that from scratch, we’d have to rely on a little calculus, namely the fact that the integral of $1/x\ dx$ is $\ln(x)+C$—slightly smirching the pleasant calculus-free accessibility of these problems.)

4

If you select three sticks, each of random length (between 0 and 1), what is the probability of being able to form an acute triangle with the sticks?

Let the lengths of the sticks be $x$, $y$, and $z$, and assume (with probability $1/3$) that $z$ is the largest of the three. They form an acute triangle so long as this inequality holds:

\[A: x^2 + y^2 > z^2\]If we think of the space of possible triples $(x, y, z)$ as points in the unit cube, then we can think of the assumption that $z$ is the largest as meaning that the point lies in the volume-$1/3$ portion $P$ of the cube in which $z$ is greater than both $x$ and $y$. And we can think of the inequality $A$ as meaning that the point lies outside of the cone $z^2=x^2+y^2$ (whose intersection with the cube is entirely within $P$).

The volume inside $P$ that is also inside the cone is a one-quarter pie-slice of a cone of height $1$ and base radius $1$. The volume of a cone is $\pi r^2 h/3$, and so the volume of the region of $P$ outside of the cone is:

\[\frac{1}{3} - \frac{\pi}{12}\]Multiplying by three to account for points where $x$ or $y$ is the largest coordinate, we find that the volume within the unit cube of every point lying outside the cone determined by the largest of the point’s coordinates is:

\[1 - \frac{\pi}{4} \approx 21.46\%\]5

If you break a stick in three places at random, forming four pieces, what is the probability of being able to form a quadrilateral with the pieces?

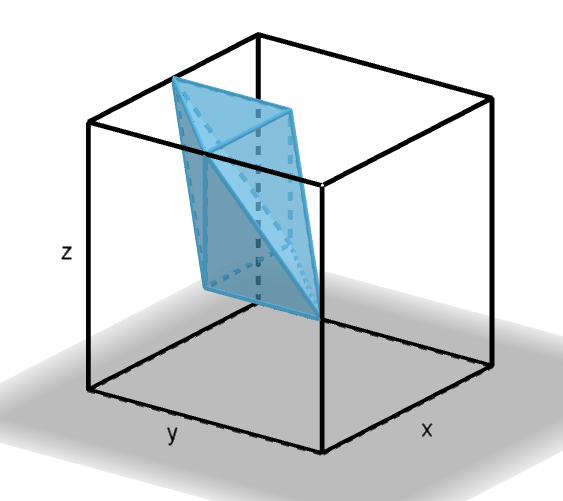

Once again, this amounts to ensuring that no piece is of length greater than $1/2$. Call the points of the breaks $x$, $y$, and $z$, and assume (with probability $1/6$) that that their numerical order is from least to greatest. Then our constraints are:

\[x > 0\] \[x < 1/2\] \[y > x\] \[y< x+1/2\] \[z>y\] \[y>z+1/2\] \[z > 1/2\] \[z < 1\]These eight constraints carve from the unit cube the facets of a diamond-shaped region composed of two pyramids with the same square base of side $1/2$ and height $1/2$.

The volume of the diamond is then twice $1/3$ times the base area $1/4$ times the height $1/2$, or $1/12$. Multiplying by $6$ for the different possible orderings of $x$, $y$, and $z$, our answer is $1/2$.

6

If you break a stick in $n$ places at random, forming $n+1$ pieces, what is the probability of being able to form a $(n+1)$-gon with the pieces?

Lay the pieces down in original order, left to right. Now consider one of the breaks, $B$. $B$ is the break to the right of a piece of length greater than or equal to $1/2$ just in case $B$ is greater than $1/2$ (probability $1/2$) and all of the other $n-1$ breaks are outside of the region between $B$ and the point $1/2$ to its left (probability $1/2^{n-1}$). So $B$’s probability of being such a break is $1/2^n$. Since each of the $n$ breaks has that chance of being to the right of a longer-than-$1/2$ piece, and so does the very right end of the stick, and no more than one of these can be, in all the chance that one of them does so is $(n+1)/2^n$. Therefore the chance that no break is to the right of such a piece, and so we can form a $(n+1)$-gon, is $1-(n+1)/2^n$.

Empirical Sanity-Check

The following Python code agrees with the above results:

from random import random

Reps = 100000000

Accum = [0]*5

for _ in range(Reps):

S = [random(),random(),random()]

S.sort()

v,u,w = S[0],S[1]-S[0],1-S[1]

Accum[0] += S[0] < .5 and S[1] > .5 and S[1]-S[0] < .5

Accum[1] += S[0] < S[1]+S[2] and S[1]<S[0]+S[2] and S[2]<S[0]+S[1]

Accum[2] += w**2<v**2+u**2 and u**2<v**2+w**2 and v**2<u**2+w**2

Accum[3] += S[2]**2 < S[0]**2+S[1]**2

Accum[4] += S[0] < .5 and S[2] > .5 and S[1]-S[0] < .5 and S[2]-S[1] < .5

print [1.0*Accum[i]/Reps for i in range(len(Accum))]