Take a look at this string of numbers:

333 2 333 2 333 2 33 2 333 2 333 2 333 2 33 2 333 2 333 2 …

At first it looks like someone fell asleep on a keyboard. But there’s an inner logic to the sequence:

Each digit refers to the number of consecutive 3s before a certain 2 appears. Specifically, the first digit refers to the number of consecutive 3s that appear before the first 2, the second digit refers to the number of 3s that appear consecutively before the second 2, and so on toward infinity.

The sequence never ends, but that won’t stop us from asking us questions about it. What is the ratio of 3s to 2s in the entire sequence?

Solution

By “the ratio of $3$s to $2$s in the entire sequence” we can only understand the limit of the ratios of $3$s to $2$s for initial segments of the sequence as those segments get larger. Let’s call that limit $r$. Then, for a very large initial segment, call it $S$, the ratio of $3$s to $2$s is essentially $r$.

The foothold that will help us find $r$ is the relation of $S$ to an important longer initial segment. The segment $S^*$ of the sequence described by $S$ contains all the $3$s and $2$s referred to by numbers in $S$. Each $3$ in $S$ describes three $3$s and a $2$, and each $2$ describes two $3$s and a $2$. The ratio of $3$s to $2$s in $S^*$, which must turn out to be $r$, is also expressible as a simple function of the ratio ($r$) of the $3$s to the $2$s in $S$ that describe them. Since the proportion of $3$s in $S$ is $r/(r+1)$ and the proportion of $2$s is $1/(r+1)$, the ratio of $3$s to $2$s in $S^*$ is:

\[3\frac{r}{r+1}+2\frac{1}{r+1} = \frac{3r+2}{r+1}\](If that doesn’t seem very intuitive, think of it as the expected or average number of $3$s preceding a $2$.)

Setting that equal to $r$ and multiplying out, we get:

\[r^2 - 2r -2 = 0\]The quadratic formula tells us that $r = 1+\sqrt{3}$, or about $2.732$. And so we’re done! Right?

Not so fast!

What we have actually shown is that, on the assumption that there is a ratio $r$ that the partial ratios (ratios of initial segments) converge to, it can only be $1+\sqrt{3}$. It’s certainly plausible that there is such a limiting ratio, and computing the ratio for initial subsequences encourages that thought, as the ratios are observed to tend quickly towards that value from above. But to be rigorous we need to prove it.

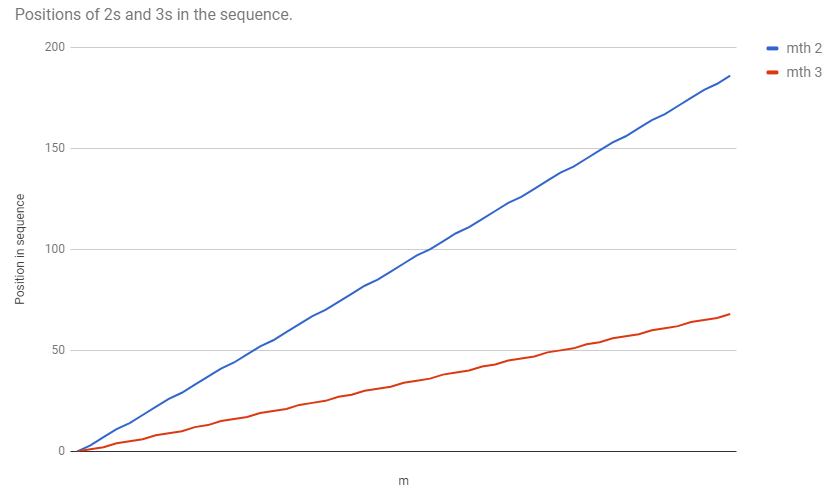

Here is a plot of the positions of $2$s and $3$s in the self-generating sequence.

(We are numbering from $m = 0$, and to clean up the math we count the initial position for both a $3$ and a $2$ as $0$—no harm, because starting the sequence with a $2$ does not change any other element of the sequence.)

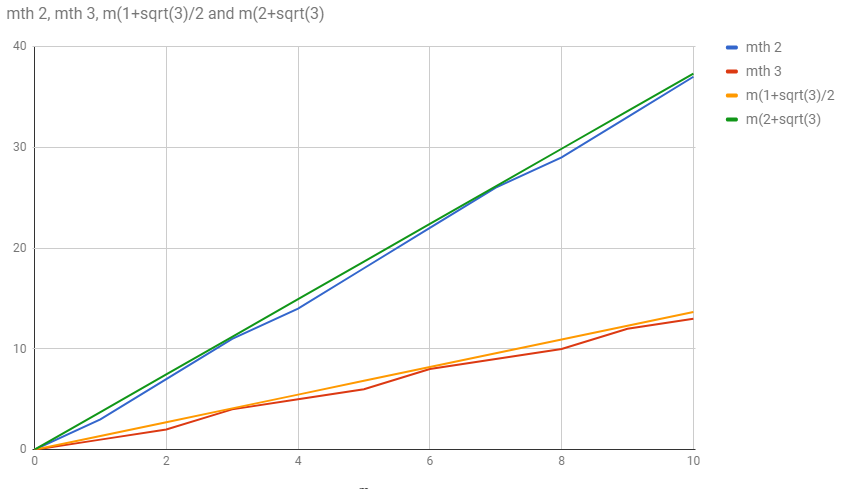

These plots sure look approximately linear, with wiggles that start small, and while they remain the same absolute size, they get less significant comparatively as you zoom out. Supposing the ratio $r$ of $3$s to $2$s is indeed $1+\sqrt{3}$, we can deduce the average slopes of these plots. The slope of the plot for $3$s is the average number of sequence positions per occurrence of a $3$, so it is the inverse of the density of $3$s in the sequence, and so it is $(1+r)/r$, or $(1+\sqrt{3})/2$. Similarly, the slope of the plot for $2$s is $2+\sqrt{3}$. Now let’s look at the same plots (in a close-up) together with the two lines that have precisely those slopes.

The plots never exactly match the lines for any non-zero $m$—they can’t because the lines, having irrational slopes, have no points with integral coordinates except the origin. But the plots diverge from the lines by less than $1$ at every $m$ we see. If that remains true for all $m$, then the plots are described by the following formulae for the position of the $m$th $2$ or $3$ (where the brackets denote the floor function, which yields the greatest integer less than or equal to its argument):

\[\left\lfloor m (2+\sqrt{3})\right\rfloor\] \[\left\lfloor m \frac{1+\sqrt{3}}{2}\right\rfloor\]Let’s prove the conjecture that the $m$th $2$ in the sequence occurs at position $\lfloor m(2+\sqrt{3})\rfloor$, or for short, $\lfloor mt \rfloor$. (Much of the proof is lifted from a solution to a Putnam Competition problem. Thanks to my brother for the link; before seeing it I had a less elegant proof of the ratio’s convergence.)

Start by stipulatively defining sequence $A=a_0,a_1,a_2,\ldots$, where $a_m$ is $2$ if for some integer $n$, $m = \lfloor nt\rfloor$, and is $3$ otherwise. We will show that (after the initial $2$) $A$ is our self-generating sequence.

The definition of our self-generating sequence is equivalent to stipulating that it’s a sequence of $2$s and $3$s that starts with a $3$ and in which a $2$ occurs at position $i$ iff the $i$th and $i+1$st $2$s are separated by $2$ rather than $3$ $3$s—that is, they are $3$ rather than $4$ positions apart. If sequence $A$ also has this property, then $A$ must be the target sequence itself.

So suppose $a_j$ is a $2$ for some $j>0$.

Then, for some integer $k>0$

\[j = \lfloor kt \rfloor\]Because $kt$ is never integral for $k>0$, we know that for some integer $k$:

\[j < kt < j+1\]Therefore, for some integer $k > 0$:

\[j/t < k < (j+1)/t\]So $j/t$ and $(j+1)/t$ flank an integer and so:

\[\lceil (j+1)/t \rceil - \lceil j/t \rceil = 1\](These brackets are the ceiling function that returns the least integer greater than or equal to its argument.)

Remembering that $t$ is $(2+\sqrt{3})$,

\[\lceil j/t \rceil = \lceil j/(2+\sqrt{3})\rceil= \left\lceil\frac{2j-2\sqrt{3}}{4-3} \right\rceil = \lceil 4j -(2+\sqrt{3})j \rceil = 4j - \lfloor tj \rfloor\]Similarly for $\lceil(j+1)/t\rceil$, and so:

\[4(j+1) - \lfloor t(j+1) \rfloor - (4j - \lfloor tj \rfloor) = 1\]Therefore:

\[\lfloor t(j+1)\rfloor - \lfloor tj \rfloor = 3\]And therefore the $j$th and $j+1$st $2$s in $A$ are $3$ positions apart. All of this reasoning is valid in both directions, so we have shown that $a_j$ is a $2$ iff the $j$th and $j+1$st $2$s in $A$ are $3$ rather than $4$ positions apart, and so $A$ is indeed our self-generating sequence.

We don’t need to similarly prove that the positions of $3$s given by $m(1+\sqrt{3})/2$ (for short, $ms$) for positive $m$ also defines the self-generating sequence, because it is easy to confirm that $1/s + 1/t = 1$, which makes the sequences generated by $\lfloor tm \rfloor$ and $\lfloor ms \rfloor$ for $m \geq 1$ Beatty Sequences, which we therefore know together contain all positive integers without repetition. So the $\lfloor ms\rfloor$ sequence for $m > 0$ must indeed contain the positions of exactly the $3$s in the self-generating sequence.

Since the plots of the positions of $2$s and $3$s differ from the lines whose slopes are $t$ and $s$ by less than $1$ at any point, which becomes a smaller and smaller fraction of the positions as $m$ grows large, the limiting average periods of $2$s and $3$s in the sequence are given by $t$ and $s$. The inverses of $t$ and $s$ are therefore the limiting densities of $2$s and $3$ in the sequence, and the ratio of those inverses, which is the ratio we’ve been looking for all along, and which after all we derived the conjectured values of $t$ and $s$ from in the first place, is $(1+\sqrt{3})$.

(Guy Moore in a comment to this post provides a more exact description of this convergence.)

Interesting facts:

- If, instead of $3$ and $2$, we use $2$ and $1$ to form the sequence (so that it starts $2,2,1,2,2,1,2,1,\ldots$), the limiting ratio of $2$s to $1$s is the golden ratio, $(1+\sqrt{5})/2$, or about $1.618$.

- These sequences do not repeat (if they did repeat, the ratios would be rational).

- The x/y ratio of these sequences is the same as their mean value.

- And it is the same as the positive first element of the eigenvector of the matrix $(x\ y; 1\ 1)$. (That’s really just a much tidier way of framing the first section of our solution.)