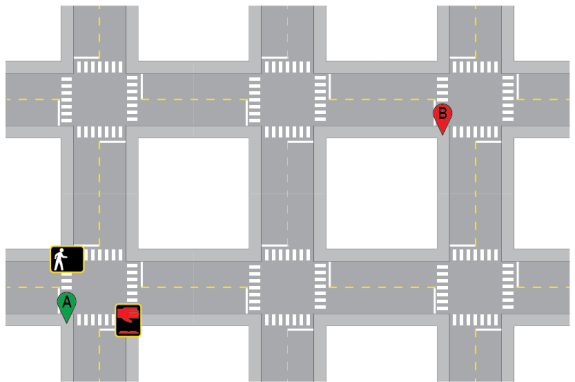

We are to walk on a rectilinear grid $N$ blocks north and $E$ blocks east, making $N$ and $E$ crossings of timed intersections. The intersections are not synchronized with each other, but there is a constant time period $T$ such that, for a given intersection, the north-south and east-west signals alternate $T/2$ intervals of displaying “GO” (we may start across) and “NO-GO” (we may not start across), along with the number of seconds until the next signal change. What should our strategy be, so as to have the lowest expected total time waiting at intersections?

(Adapted from the Riddler at fivethirtyeight)

Solution

Give the intersections coordinates: we start at $(E,N)$, with $E$ and $N$ more intersections to cross going east and going north, and we finish at $(0,0)$. A strategy for a given intersection is a decision about what to do, based on what is displayed on the signals. We choose units of time so that $T$ is two units, and we can represent a strategy as a number $S(e,n)$ between $-1$ and $1$. This number represents the difference between the expected remaining total wait after crossing intersection $(e,n)$ if we go north versus east there. That is, it is the expected advantage of going east. If, $S(e,n)$ is, say, $.35$, that means that we should go east unless east’s signal is “NO-GO” and has a time-until-GO of more than $.35$ units. Negative strategies represent a corresponding preference for going north.

We can start by assuming that, for every $e$, $S(e,0)$ is $1$: when we have reached the destination east-west street, we wait to go east no matter what. (This assumption makes sense as long as $T$ is not very large compared to the time it takes to walk a block.)

Another simple case is an intersection of the form $(i,i)$; by symmetry, neither direction is preferable, and so it is always best to cross in whichever direction is open. Therefore, $S(i,i)$ is $0$. While we won’t need to rely on this observation, it will help us understand our results.

As we will see, for every other, “non-trivial,” intersection $(e,n)$, best-strategy depends on the expected total waits, given optimal strategy, from each of the two possible next intersections $(e-1,n)$ and $(e,n-1)$.

The expected wait time at a given intersection, $W(e,n)$ is a function of its strategy. At an intersection with strategy $s$, the only situations in which we wait are those $|s|/2$ of cases in which we find the preferred-direction signal showing “NO-GO” and less than $|s|$ units to “GO.” Our average wait in those cases is also $|s|/2$, and so:

\[W(e,n) = S(e,n)^2/4\]Call $E(e,n)$ the expected total wait time remaining, given optimal strategy, on arrival at intersection $(e,n)$. Start with “trivial” intersections of the form $(e,0)$. $E(e,0)$ is $e$ times the expected wait for an intersection’s east signal to display “GO.” Half of the time, the signal already displays “GO,” and the other half of the time, it averages $.5$ units until “GO,” so the expected wait is $.25$, and so $S(e,0)$ is $e/4$. Similarly, for every $n$, $E(0,n)$ is $n/4$.

For non-trivial intersections, $E(e,n)$ is calculated from $W(e,n)$, which is the expected wait time at the intersection itself, plus a weighted sum of $E(e-1,n)$ and $E(e,n-1)$, weighted by how likely it is, given the strategy $S(e,n)$, that we’ll cross to the east and to the north:

\[E(e,n) = W(e,n) + \frac{1 + S(e,n)}{2}E(e-1,n) + \frac{1 - S(e,n)}{2}E(e,n-1)\]And we calculate strategies for such intersections as follows. So long as the expected total remaining waits at the two possible next intersections are within $1$ of each other:

\[S(e,n) = E(e,n-1) - E(e-1,n)\]But if that value is less than $-1$ or greater than $1$, then $S(e,n)$ is $-1$ or $1$.

It’s a little complicated, but the upshot is that for non-trivial intersections we can calculate $E(e,n)$ from just $E(e-1,n)$ and $E(e,n-1)$. This gives us a recurrence that lets us find, starting with the trivial expectations, $E(e,n)$ and $S(e,n)$ for any $(e,n)$.

The Python code below implements this. Values up to $(20,10)$ are displayed below. The resulting strategy always to some degree favors heading in the direction, if there is one, that brings the coordinates closer together; that is, heading towards the $e = n$, $45$-degree “centerline.” That’s probably because there is no waiting at centerline intersections, and when we’re close to that line we can normally afford to choose whichever direction is open, again with no wait. The extent that one should be willing to wait in order to head in that direction is roughly proportional to the angle between the centerline and one’s own straight line to the finish. If that angle is small, only wait small amounts; if big, wait substantial amounts (if $45$-degrees, of course, you have to wait however long it takes).

I was surprised to find that in traversing an entire $20$ by $10$ grid, which means crossing thirty intersections, the expected wait is just $1.5$ times the length of a single “NO-GO” period. (I was surprised enough to take the trouble to verify it with a Monte Carlo simulation.) In contrast, if we insisted on walking all the way east and then all the way north, our expected total wait would be $30/4$ or $7.5$ “NO-GO” periods, which is five times as much waiting time.

The actual 538Riddler question was to find the best moves for starting at intersection $(2,1)$ with one second remaining on the NO-GO east signal.

The answer in our grid is the strategy of $.25$, i.e., cross east if it’s a “GO,” or wait for the east signal to allow you to cross unless there’s more than $.25$, which is a quarter of the “NO-GO” time, or $T/8$, left on its clock. To walk through the reasoning that gets us there, we are choosing between crossing north, where we’d have an expected $.5$ remaining total wait time, or east, where we’d have just $.25$ more expected wait. Waiting to cross east makes sense as long as we don’t have to wait more than $.25$ to do it, which would make it cost more than it saves. So the answer is that, so long as one second is less than $T/8$ (that is, so long as the signals take more than four seconds to switch, which is a pretty safe assumption), wait and go east, young man.

Wait-Time Expectations

| 20 | 19 | 18 | 17 | 16 | 15 | 14 | 13 | 12 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5.00 | 4.75 | 4.50 | 4.25 | 4.00 | 3.75 | 3.50 | 3.25 | 3.00 | 2.75 | 2.50 | 2.25 | 2.00 | 1.75 | 1.50 | 1.25 | 1.00 | 0.75 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.00 |

| 1 | 4.40 | 4.16 | 3.92 | 3.67 | 3.43 | 3.19 | 2.95 | 2.71 | 2.48 | 2.24 | 2.01 | 1.78 | 1.55 | 1.33 | 1.11 | 0.90 | 0.70 | 0.52 | 0.36 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| 2 | 3.89 | 3.65 | 3.42 | 3.19 | 2.96 | 2.73 | 2.50 | 2.28 | 2.06 | 1.85 | 1.63 | 1.43 | 1.23 | 1.04 | 0.86 | 0.69 | 0.55 | 0.43 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.50 |

| 3 | 3.44 | 3.21 | 2.99 | 2.77 | 2.56 | 2.34 | 2.13 | 1.93 | 1.73 | 1.53 | 1.34 | 1.17 | 1.00 | 0.84 | 0.70 | 0.58 | 0.49 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.52 | 0.75 |

| 4 | 3.04 | 2.83 | 2.62 | 2.41 | 2.21 | 2.02 | 1.82 | 1.64 | 1.46 | 1.29 | 1.12 | 0.97 | 0.83 | 0.71 | 0.61 | 0.53 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.55 | 0.70 | 1.00 |

| 5 | 2.69 | 2.49 | 2.30 | 2.11 | 1.92 | 1.74 | 1.57 | 1.40 | 1.24 | 1.09 | 0.96 | 0.83 | 0.72 | 0.63 | 0.57 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.58 | 0.69 | 0.90 | 1.25 |

| 6 | 2.39 | 2.20 | 2.02 | 1.84 | 1.68 | 1.51 | 1.36 | 1.21 | 1.07 | 0.95 | 0.83 | 0.74 | 0.66 | 0.60 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.61 | 0.70 | 0.86 | 1.11 | 1.50 |

| 7 | 2.12 | 1.95 | 1.78 | 1.62 | 1.47 | 1.32 | 1.19 | 1.06 | 0.94 | 0.84 | 0.75 | 0.68 | 0.63 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.63 | 0.71 | 0.84 | 1.04 | 1.33 | 1.75 |

| 8 | 1.88 | 1.73 | 1.58 | 1.43 | 1.29 | 1.17 | 1.05 | 0.94 | 0.85 | 0.76 | 0.70 | 0.65 | 0.63 | 0.63 | 0.66 | 0.72 | 0.83 | 1.00 | 1.23 | 1.55 | 2.00 |

| 9 | 1.68 | 1.54 | 1.40 | 1.27 | 1.15 | 1.04 | 0.94 | 0.85 | 0.78 | 0.72 | 0.68 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.68 | 0.74 | 0.83 | 0.97 | 1.17 | 1.43 | 1.78 | 2.25 |

| 10 | 1.50 | 1.37 | 1.25 | 1.14 | 1.04 | 0.94 | 0.86 | 0.79 | 0.74 | 0.70 | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.70 | 0.75 | 0.83 | 0.96 | 1.12 | 1.34 | 1.63 | 2.01 | 2.50 |

Strategies

| 20 | 19 | 18 | 17 | 16 | 15 | 14 | 13 | 12 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| 1 | 0.84 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.82 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.77 | 0.76 | 0.74 | 0.72 | 0.70 | 0.67 | 0.64 | 0.60 | 0.55 | 0.48 | 0.39 | 0.25 | 0.00 | -1.00 |

| 2 | 0.75 | 0.74 | 0.73 | 0.72 | 0.70 | 0.69 | 0.67 | 0.65 | 0.63 | 0.61 | 0.58 | 0.55 | 0.51 | 0.47 | 0.42 | 0.35 | 0.27 | 0.16 | 0.00 | -0.25 | -1.00 |

| 3 | 0.68 | 0.66 | 0.65 | 0.63 | 0.62 | 0.60 | 0.58 | 0.55 | 0.53 | 0.50 | 0.47 | 0.43 | 0.39 | 0.34 | 0.28 | 0.21 | 0.12 | 0.00 | -0.16 | -0.39 | -1.00 |

| 4 | 0.61 | 0.59 | 0.58 | 0.56 | 0.54 | 0.52 | 0.50 | 0.47 | 0.44 | 0.41 | 0.37 | 0.33 | 0.29 | 0.23 | 0.17 | 0.09 | 0.00 | -0.12 | -0.27 | -0.48 | -1.00 |

| 5 | 0.55 | 0.53 | 0.51 | 0.49 | 0.47 | 0.45 | 0.42 | 0.39 | 0.36 | 0.33 | 0.29 | 0.25 | 0.20 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.00 | -0.09 | -0.21 | -0.35 | -0.55 | -1.00 |

| 6 | 0.49 | 0.47 | 0.45 | 0.43 | 0.41 | 0.38 | 0.36 | 0.33 | 0.30 | 0.26 | 0.22 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.00 | -0.08 | -0.17 | -0.28 | -0.42 | -0.60 | -1.00 |

| 7 | 0.44 | 0.42 | 0.40 | 0.38 | 0.35 | 0.33 | 0.30 | 0.27 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.00 | -0.07 | -0.14 | -0.23 | -0.34 | -0.47 | -0.64 | -1.00 |

| 8 | 0.39 | 0.37 | 0.35 | 0.33 | 0.30 | 0.27 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.00 | -0.06 | -0.12 | -0.20 | -0.29 | -0.39 | -0.51 | -0.67 | -1.00 |

| 9 | 0.35 | 0.33 | 0.30 | 0.28 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.00 | -0.05 | -0.11 | -0.17 | -0.25 | -0.33 | -0.43 | -0.55 | -0.70 | -1.00 |

| 10 | 0.31 | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.00 | -0.05 | -0.10 | -0.16 | -0.22 | -0.29 | -0.37 | -0.47 | -0.58 | -0.72 | -1.00 |

Code (Python)

E = 20

N = 10

Exp = {}

# Populate trivial expectations

for e in range(E+1):

Exp[(e,0)] = e/4.0

for n in range(N+1):

Exp[(0,n)] = n/4.0

# Now the non-trivial ones

for e in range(1,E+1):

for n in range(1,N+1):

EE = Exp[(e-1,n)]

EN = Exp[(e,n-1)]

Strategy = EN - EE

if Strategy < -1:

Strategy = -1

if Strategy > 1:

Strategy = 1

WaitTimeHere = Strategy**2/4

Exp[(e,n)] = WaitTimeHere + EE*(1+Strategy)/2 + EN*(1-Strategy)/2