The classic birthday problem asks about how many people need to be in a room together before you have better-than-even odds that at least two of them have the same birthday. Ignoring leap years, the answer is, paradoxically, only 23 people — fewer than you might intuitively think.

But Joel noticed something interesting about a well-known group of 100 people: In the U.S. Senate, three senators happen to share the same birthday of October 20: Kamala Harris, Brian Schatz and Sheldon Whitehouse.

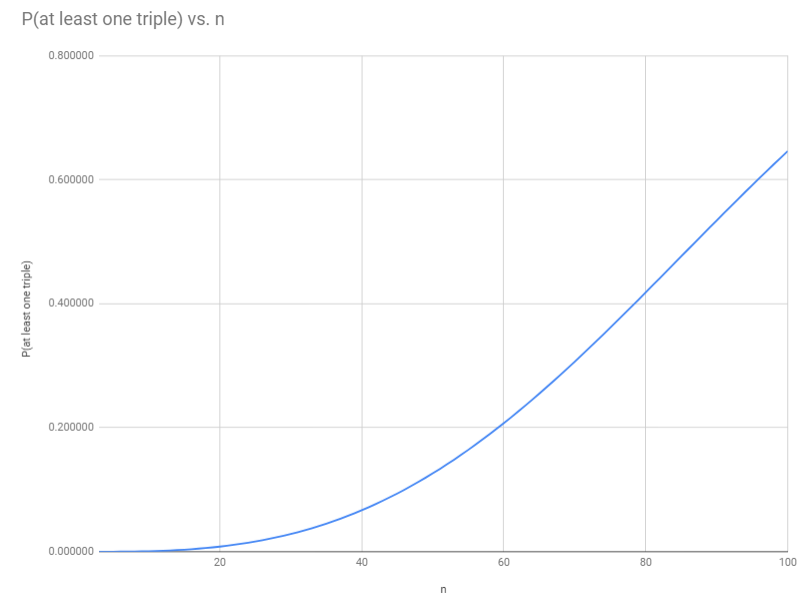

And so Joel has thrown a new wrinkle into the classic birthday problem. How many people do you need to have better-than-even odds that at least three of them have the same birthday? (Again, ignore leap years.)

Solution

This is an exercise in combinatorics. For a group of $n$ people, there are $365^n$ possibilities — all equally likely — for what all of their individual birthdays might be. If we can count the number of these possibilities in which there are at least three people with the same birthday, we divide and we’re done.

The possibilities in which at least three people have the same birthday are all those besides those in which: there is no such “triple” and also no “doubles,” or there is no triple and exactly $1$ double, or there is no triple and $2$ doubles, and so on up to no triple and exactly $n/2$ or $(n-1)/2$ doubles (for $n$ even or odd; equivalently we can write this as $\lfloor{n/2}\rfloor$, using the floor function, which yields the greatest integer less than or equal to its argument). So let’s count the possibilities that, among $n$ people, there are no triples and exactly $k$ doubles.

There is one such possibility for every way of answering the following three questions: who are the doubled pairs? what birthdays do these paired people have? what birthdays does everyone else have? The number of possibilities will be a product: the numbers of ways of answering the first question times the number of ways of answering the second (given an answer to the first) times the number of ways of answering the third (given answers to the first and second).

1. Who are the paired people?

It will be easiest first to count how many ways of writing a list of $k$ pairs there are. This is easy: we have $n$ choices for the first person listed, $n-1$ for the second, and so on down to $n-2k+1$ for the last; the product of these numbers is the number of lists.

This will over-count ways of pairing people into $k$ pairs, and in two ways. Given any list, we get equivalent lists for any of the $2^k$ ways of switching first and second within pairs, and we get an equivalent list for any of the $k!$ permutations of the listed pairs. So, having counted lists of pairs, we divide by $2^kk!$ to yield the number of ways of answering our first question:

\[\frac{\prod_{i=0}^{2k-1} n - i }{2^kk!}\]2. What birthdays do these paired people have?

Start with an arbitrary listing of the $k$ pairs. To assign them birthdays, there are $365$ options for the first pair, $364$ for the second, and so on down to $365-k+1$ options for the last. The total number of ways of assigning the pairs distinct birthdays, then, is the product of all of these, or:

\[\prod_{i=0}^{k-1} 365 - i\]3. What birthdays does everyone else have?

There are $365-k$ birthdays left, and we have to distribute $n-2k$ of them to the remaining $n-2k$ people. Reasoning exactly as we just did in answering the second question, we count the number of ways of doing this:

\[\prod_{i=0}^{n-2k-1} 365-k -i\]Finishing up

The product of our answers to the three questions for a particular $k$, remember, is the total number of possibilities in which there are no triples and exactly $k$ doubles. The sum $S$ of these products for all $k$ from $0$ to $\lfloor{n/2}\rfloor$ is the total number of possibilities in which there are no triples. Then $S/365^n$ is the probability that there are no triples, and $1 - S/365^n$ is the probability that there is at least one triple.

Computationally, we find that this probability first exceeds $.5$ when $n$ is $88$.