I have $N$ pairs of socks in a drawer. I pull out socks (without replacement) until I have a matching pair. On average, how many socks does it take?

Extra Credit: describe the behavior of this average for large $N$.

Solution

A recurrent approach

Given $N$ pairs of socks, let $E_i$ be the expected number of (additional) socks you’ll have to pull out to get a match, given that you have already pulled out $i$ non-matching socks.

Then, $E_N$ is $1$, because when you have pulled out $N$ non-matching socks — one from each pair — you are certain to get a match on the next try.

Suppose you have pulled out $i$ socks, for $0 \leq i < N$. Then your probability of getting a match on the next try is $i/(2n-i)$. If you fail to get a match, you will then expect $E_{i+1}$ more tries. Therefore:

\[E_i = \frac{i}{2N-i} + \frac{2N-2i}{2N-i} \cdot (1 + E_{i+1})\]This lets us calculate $E_i$ for any $i$, down to $E_0$, which is the overall expected number of pulled-out socks. In the case of $N=10$, it’s about $5.68$ socks.

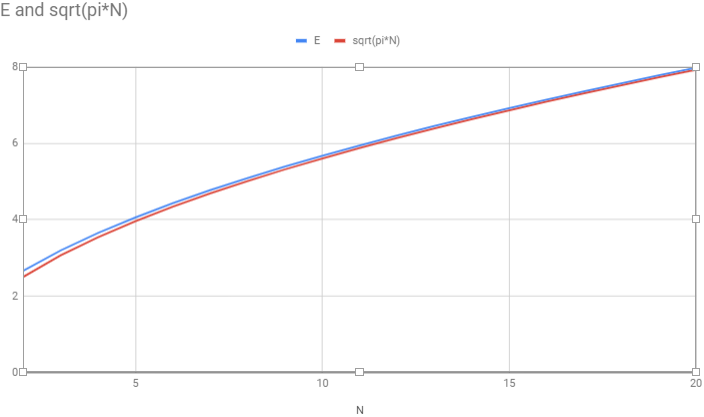

Because this approach doesn’t require computing factorials, it’s manageable to find the expectation for pretty large $N$. Doing so, we notice a pattern: the curve of $E$ versus $N$ looks like a scaled version of $\sqrt{N}$. Dividing the computed values of $E$ by $\sqrt{N}$, we find that, indeed, the ratio seems to approach a constant, which . . . is the square root of $\pi$!

Why pi? Nothing about our recurrence relation seems to promise any insight into this, so we’ll try a different approach.

A combinatorial approach, and extra credit

With $N$ pairs of socks in the drawer, we will calculate the expected value $E(X)$ of the random variable $X$, the number of pulls to yield the first pair. We will rely on the useful fact that for a non-negative, integer-valued random variable:

\[E(X) = \sum_{i=0}^\infty P(X > i)\]So let’s find $P(X>i)$. There are ${2N \choose i}i!$ ways for the first $i$ pulls to go (choices of the socks multiplied by the number of their orderings), out of which some are ways in which no pair occurs. How many? There are ${N \choose i}$ choices of pairs to have already pulled a sock from, there are $2^i$ choices of particular socks from those pairs, and there are $i!$ orderings of those socks. So:

\[P(X>i) = \frac{ {N \choose i} 2^ii!}{ {2N \choose i} i!} = {2N \choose N}^{-1}{2N-i \choose N} 2^i\]Because the greatest $i$ for which $P(X>i)$ is non-zero is $N$:

\[E(X) = {2N \choose N}^{-1}\sum_{i=0}^N {2N-i \choose N} 2^i\]Pi comes into the picture because the central binomial coefficient $2N \choose N$ asymptotically approaches $4^N/\sqrt{\pi N}$. There is a nice proof of that fact relying on just elementary math supplemented by the Wallis Product formula for $\pi$:

\[\frac{2}{1}\cdot\frac{2}{3}\cdot\frac{4}{3}\cdot\frac{4}{5}\cdot\frac{6}{5}\cdot\frac{6}{7}\cdots = \frac{\pi}{2}\]This equation itself can be proven in a really cool, demystifying way “using only the mathematics taught in elementary school, that is, basic algebra, the Pythagorean theorem, and the formula $\pi r^2$ for the area of a circle of radius $r$.” Don Knuth walks us through Johan Wästlund’s proof in a fun lecture called “Why Pi?” that I definitely recommend viewing).

It remains to evaluate the sum:

\[\sum_{i=0}^N {2N-i \choose N} 2^i\]Think of this sum as an absurdly complex, but entirely correct, way of answering the question, how many different heads/tails sequences are there for $2N$ flips of a coin?

At some point in any such sequence, somewhere between flips $N$ and $2N$ (inclusive), the greatest of the tallies of heads and tails is $N$ for the last time in the sequence. Suppose that happens at flip $2N-i$, when $i \neq 0$, with heads in the lead. There are ${2N-i} \choose N$ ways that the first $2N-i$ flips might have gone. Because this is the last flip with a leading tally of $N$, the next flip will be heads, after which there are $i-1$ flips that can turn out as you please. Thus there are ${2N-i \choose N}2^{i-1}$ ways for that to happen with heads in the lead and similarly for tails, for a total of ${2N-i \choose N}2^i$ ways. In the case of $i = 0$, there are also ${2N -i \choose N}2^i$ ways, corresponding to the ${2N \choose N}$ choices of flips to be heads. Thus, our sum counts all the heads/tails sequences of length $2N$, and of course there are $2^{2N}$, or $4^N$ of them, and so that’s its value.

It follows that $E(X) \sim \sqrt{\pi N}$, just as we noticed computationally. Cool, no?